I recently asked Lorien Jollye if she could write a post for us on vaping advocacy. Lorien’s a great advocate, and like many other advocates she’s digging deep into her pockets to campaign for e-cigarettes. The pressures are big - Lorien and others are constantly travelling to conferences and giving talks on e-cigs, and that costs money.

Unfortunately, the answer was no. Lorien explained:

“I’d love to. Unfortunately, the moment I take any paid money from the e-cigarette industry I’ll immediately be labelled a tobacco industry shill.”

Lorien’s not the first one to tell me this. Clive Bates has devoted a huge amount of time to e-cigarette advocacy, but cannot take a penny for his efforts.

But what about our opponents? Fergus Mason investigates.

The big news in August was the release of Public Health England’s report into the health impact of electronic cigarettes.

Highly positive, and dismissive of “gateway” concerns and the recent formaldehyde scares, many vapers saw it as a game-changing piece of research that surely would be authoritative enough to convince the remaining doubters. After all this wasn’t just another small study of what happens to mice when you stuff them in a box and pump it full of vapour; this was a comprehensive review of all the current evidence by the government’s lead health agency. You would think that would be good enough to satisfy anyone with a genuine interest in public health. Unfortunately that isn’t quite how it turned out.

Highly positive, and dismissive of “gateway” concerns and the recent formaldehyde scares, many vapers saw it as a game-changing piece of research that surely would be authoritative enough to convince the remaining doubters. After all this wasn’t just another small study of what happens to mice when you stuff them in a box and pump it full of vapour; this was a comprehensive review of all the current evidence by the government’s lead health agency. You would think that would be good enough to satisfy anyone with a genuine interest in public health. Unfortunately that isn’t quite how it turned out.

Within days of the report’s publication it came under attack; firstly in the editorial column of The Lancet, then through a series of slanted media articles and finally in the British Medical Journal. The identity of the principal attackers wasn’t much of a surprise - Martin McKee and Simon Capewell, both known for their unrelenting dislike of vaping.

What was really informative was the nature of their criticism. Despite the title of their BMJ piece they didn’t even attempt to challenge the mass of evidence presented by the report; instead they aimed to discredit it by questioning the motives of the report authors. This is a classic ad hominem attack, more colloquially known as “playing the man, not the ball”, and it’s a logical fallacy.

Specifically, McKee and Capewell focused on a single sentence in the report – its statement that the estimated 95% risk reduction from switching to vaping seemed reasonable – and tried to taint its source by claiming conflict of interest. Their gripe was that some of the team who came up with that figure had financial conflicts of interest that, by implication, made their statements on e-cigarettes unreliable.

Conflicts of Interest: A Serious Issue

Now, conflicts of interest are a serious issue in research. Science has to be objective and impartial or it’s not science; it’s just lobbying. There have been too many high-profile scandals involving “research” that turned out to have been bought and paid for in advance by someone with money at stake. For example most people in the UK will remember the MMR vaccine affair, when Dr Andrew Wakefield published a paper showing a link between the vaccine and autism in children.What the paper didn’t show was that Wakefield had been paid more than £400,000 by lawyers planning to sue the vaccine’s manufacturer, and that he’d recently taken out a patent on a new, single-dose measles vaccine. Combined with the fact nobody else had been able to replicate his test results it was obvious that Wakefield had basically made it all up for money. He’s now been struck off and lives in America, where he’s a hero to the sort of people who take their children to measles parties. It’s worth noting that his paper was published in The Lancet, and that it was twelve years before the journal disowned it.

So conflicts of interest in science exist and they can be very bad news – people have died because of Andrew Wakefield’s lies.Did E-Cig Industry Pay Off UK Government Agency?

How does that relate to the PHE report though? Did Big Vapour buy off an executive agency of the British government to gloss over the harms of e-cigarettes?Well, not exactly. The claim that vaping is 95% safer than smoking came from a panel chaired by drug expert Professor David Nutt.

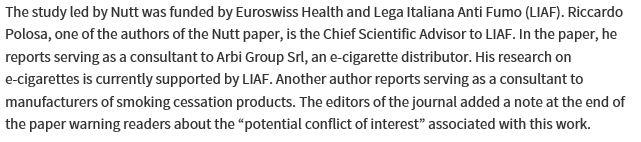

There were eleven panel members; McKee and Capewell identified one of them, Riccardo Polosa, as having a conflict of interest based on the fact that he’s done consultancy work for an e-cigarette company, he’s also done work for Italian anti-smoking organisation LIAF, and that LIAF helped fund Nutt’s study. This is an incredibly flimsy claim, especially when you consider that it’s all they have against the most comprehensive review of vaping ever conducted:

Note how the fact that a potential conflict of interest was declared is highlighted, as if this is something concerning. In fact, as we’ll see, it’s perfectly routine. The “smoking cessation products” the other author consulted on weren’t e-cigarettes, by the way – it was NRT, manufactured by the major pharma companies, and they certainly aren’t fans of vaping.Astro-Turf Accusations

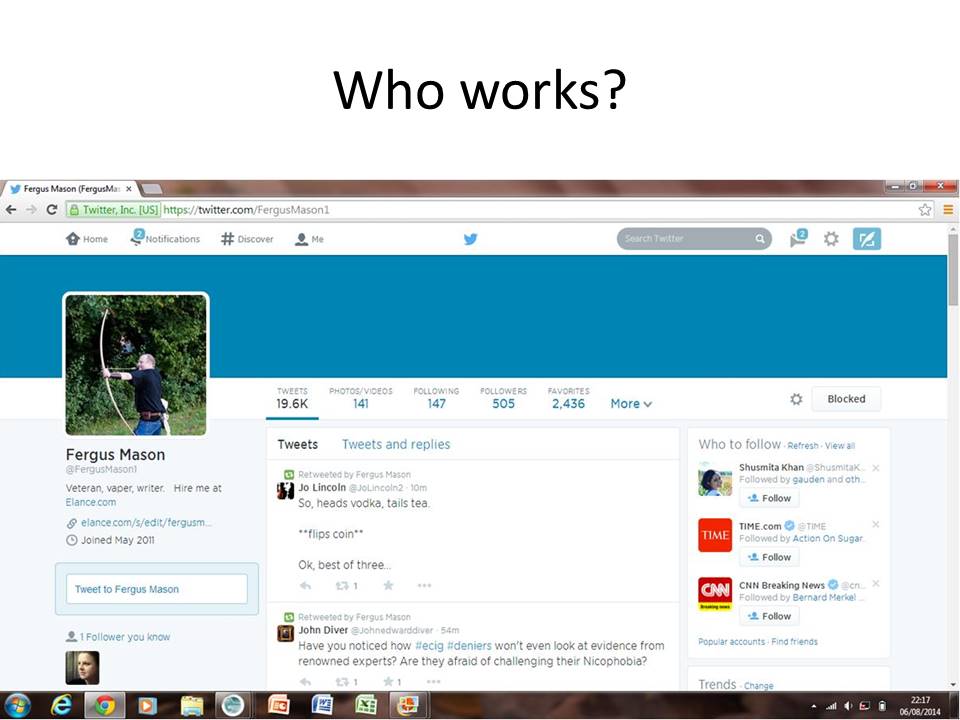

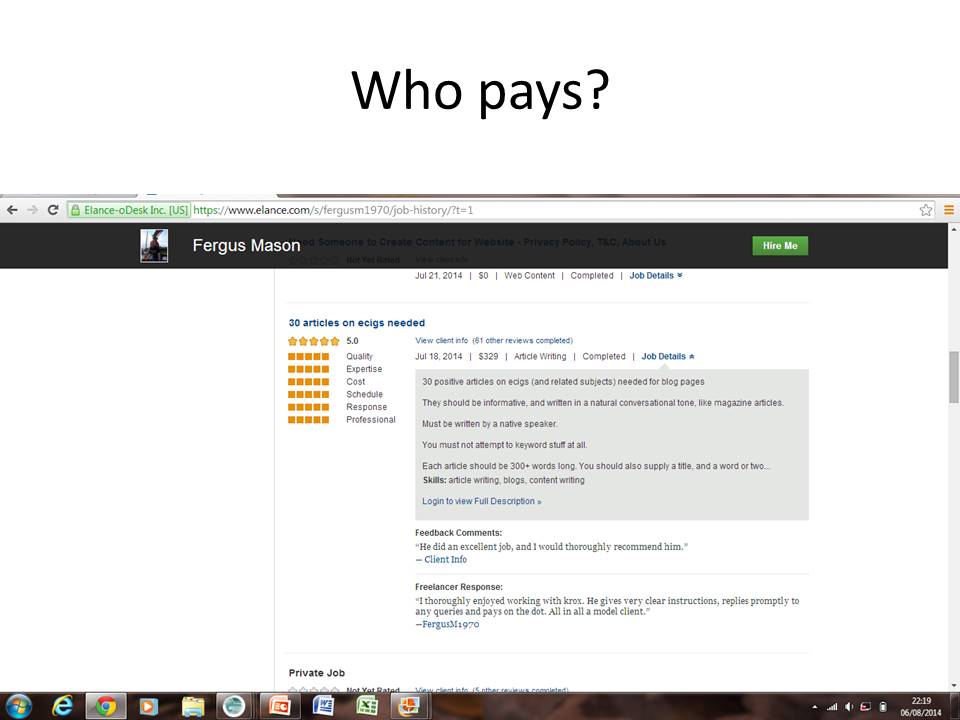

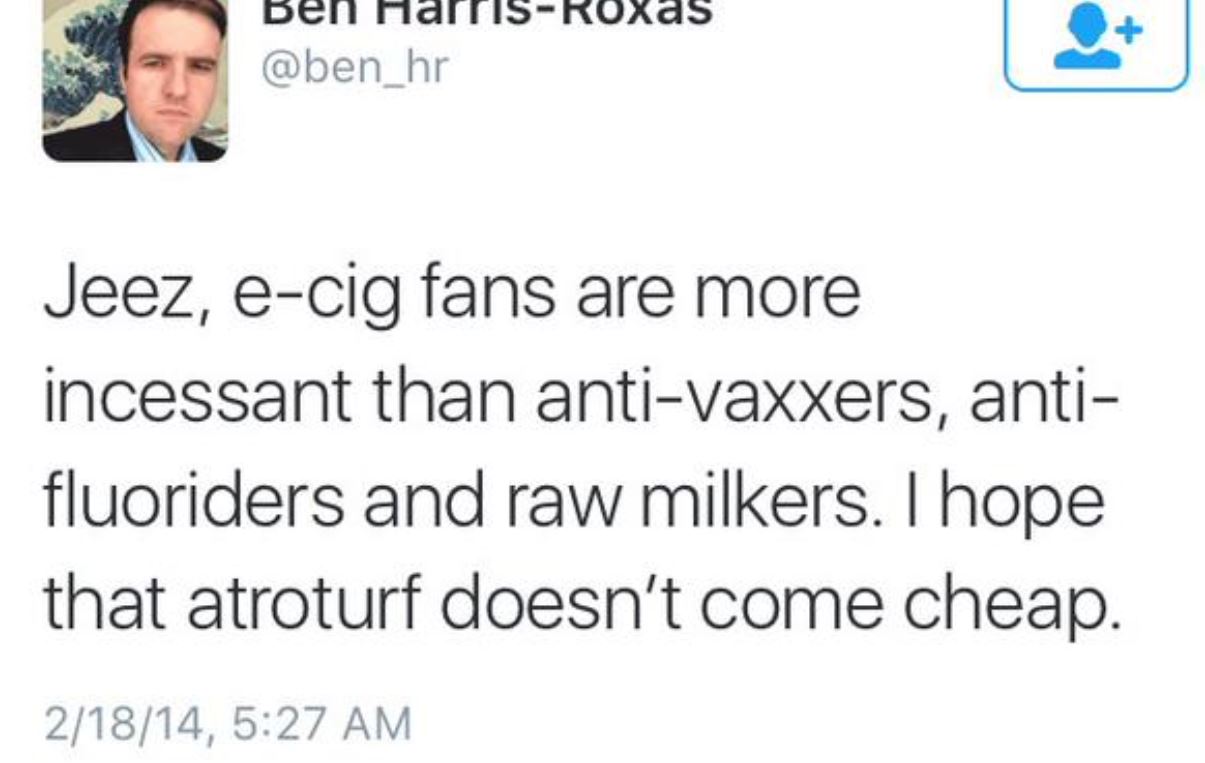

Polosa is far from the only person who has argued in favour of vaping and, in retaliation, been accused of being in the pay of the e-cigarette industry. It’s even happened to me. Last September a presentation at a public health conference in the UK contained these two slides:The implication of these two screenshots is clear: That I’m writing positive articles about vaping because I’m paid to, and therefore I’m just AstroTurf. The aim is to discredit anyone who speaks out by labelling them as a paid mouthpiece for the industry, and not a genuine activist at all.

Of course it’s a classic case of putting the cart before the horse. I’m a freelance writer, and I make my living writing whatever people pay me for. Yes, I’ve been paid to write about vaping, and I haven’t exactly tried to hide that. In fact I’ve been very open about it. The truth is that people get in touch to ask if I can write about vaping for them because I was already writing about vaping. Since I switched to e-cigarettes in 2013 I’ve been very vocal on the subject. I make my opinions known on social media, in newspaper comment sections and through blog posts. I’m also not difficult to find online, so it’s not surprising that people who want vaping-related work often contact me.

The slides, by the way, are from a presentation by Martin McKee. I just thought I’d throw that in there for anyone who enjoys looking for patterns.

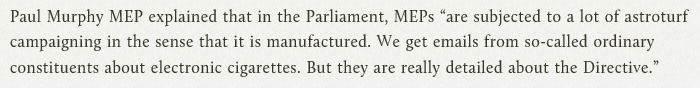

Anyway, as I said, this sort of accusation is fairly standard from the more zealous factions of the tobacco control industry and its supporters. All it takes to get called AstroTurf is to know what you’re talking about, as we can see from this rant by an Irish socialist MEP:

The implication is that if you’re interested enough in a law to actually read it then you’re not really an ordinary constituent, and have been manufactured by industry. Murphy’s comments were made to a Brussels NGO, but similar abuse is common on Twitter. Here’s Frozen Warning, a troll who’s friendly with some US anti-vapers:

Why Pays Who?

There’s a two-stage tactic at work here.The first stage is to make the claim that everyone who argues in favour of e-cigarettes is being paid to do so by the industry.

The second is to imply that any hint of industry funding means research is biased and untrustworthy. Coming from a collection of researchers and academics the second part of this is very strange indeed; after all it’s quite hard to find a professor who hasn’t done paid consultancy work for industry at some point, and there are very good reasons for this.

Most of the leading experts in any field work at universities. The universities pay them a salary for teaching, but they’re expected to fund their actual research themselves. Researchers spend a lot of their time searching for grants and a lot of those grants come from industry or other interested organisations.

It would be great if all research was carried out in a disinterested spirit of pure scientific inquiry, but those days are gone. Once, major discoveries were made by wealthy eccentrics like Charles Darwin, studying how mice attacked his beehives or sitting in his study peering at barnacles through a microscope. Modern scientists need expensive equipment and assistants who have to be paid.

An obvious source of funding is consultancy work. If a company needs some scientific analysis done the fee you get from that can then be used to fund your own research. That research doesn’t have to be related; for example Riccardo Polosa’s consulting work was into the effectiveness of e-cigarettes as a quit aid, while the Nutt panel he sat on was looking at how safe they are. We can ignore his consulting work for LIAF because LIAF is an anti-smoking group and clearly has no interest in increasing tobacco use.

There’s another way to get funding, of course. If you want to research something the chances are some company is going to be interested in the results, so you can write them a grant application to ask them to support your research (as a freelance writer I see researchers wanting grant applications written every day). Obviously this does create the potential for a conflict of interest; an unscrupulous company could apply pressure to get the result they want to see. This is why academia has strict rules about disclosing funding, to the point where – like Polosa did – scientists even declare funding they received for something else entirely.

A note at the bottom of a research paper declaring a conflicting interest doesn’t mean the research is tainted – if it did we wouldn’t have much reliable research at all. What it does mean is that other researchers can look for experimental methods, or analysis of the results, where bias might have crept in. So far from showing sinister intent, as The Lancet editorial implies, declared conflicts of interest are really a safety mechanism that guards against corrupted results.Who Pays Anti-Vaping Advocates?

Undeclared conflicts of interest, naturally, are a massive red flag. There are only two reasons for hiding a source of funding and both are enough to instantly cast doubt on the validity of the research. One is that the researcher has indeed slanted the results to suit his funders, and knows that the scrutiny given to conflicts of interest would reveal that. The other is that the source of funding is so egregiously biased that no reputable journal would even publish the paper.Wakefield is a good example here – the people who paid for his research wanted evidence they could use against the vaccine manufacturer in court. This is why Californian “health watchdog” Center for Environmental Health released their “research” into formaldehyde in e-cig vapour as a press release; CEH make their money by suing manufacturers, and the conflict of interest here is so blatant no journal would touch it with a bargepole.

McKee and the other vaping critics are always happy to insinuate outrageous conflicts of interest, such as that vaping advocates are actually astroturf, but their attacks on academics like Polosa are potentially a lot more harmful. Annoyingly, they’re also hypocritical – because they do research too, and the people who fund it often have a massive financial interest in seeing e-cigarettes fail.

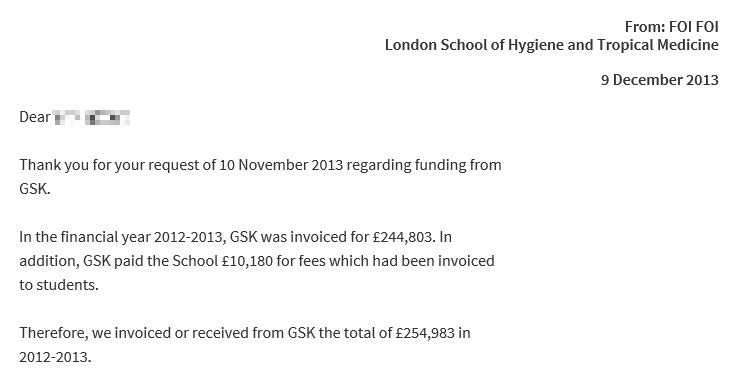

Let’s look at Martin McKee, for example. McKee is a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He has frequently denied receiving any funding from the pharmaceutical industry, and as far as anyone can tell he hasn’t personally been given any cash by makers of old-style stop smoking products. But what about his faculty? That’s a different story. They’re subject to freedom of information requests, and one was duly filed:

So LSHTM receives a quarter of a million pounds a year from the US distributor of Nicorette products, and one of its senior professors launches a bitter – almost crazed – campaign of disinformation against a competing product. It could be coincidence, of course, but if a pattern of pharmaceutical industry funding emerged that would seem less likely.

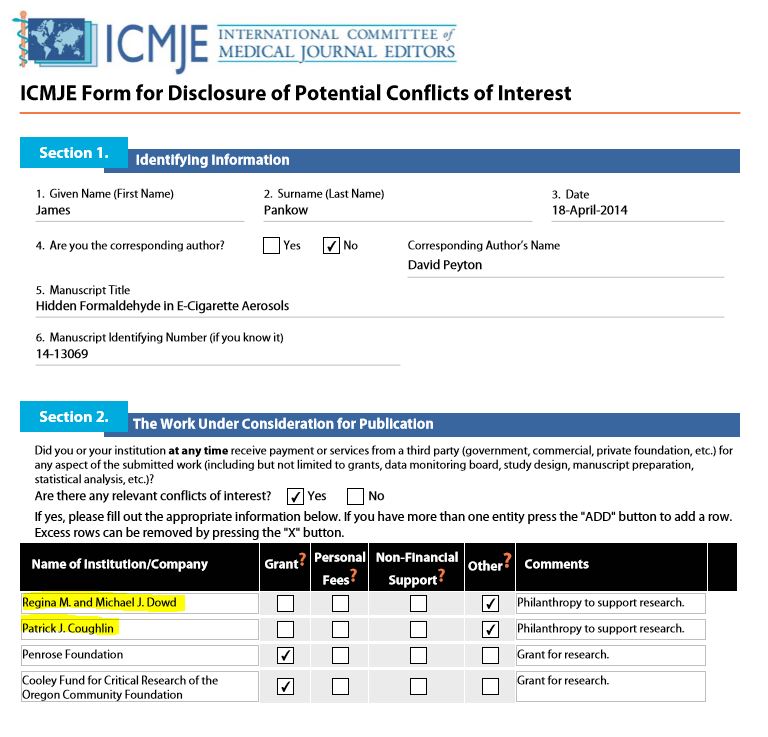

So let’s move on to the scientists behind January’s New England Journal of Medicine formaldehyde scare. The paper that really propelled this issue into the media wasn’t really a paper at all – the authors apparently didn’t want it subjected to peer review, so they submitted it as a letter to the editor instead. COI disclosure forms are available though and they’re interesting. Five scientists took part in the research and two of them – including James Pankow, the one who did most to push it in the media – received funding from the same three people:

Hmm, “philanthropy to support research”. So Patrick Coughlin and the Dowds are scientifically-minded philanthropists? No, they’re not. They’re lawyers, working for a firm that specialises in class action suits. Just like CEH and the people who bankrolled Wakefield.

What about Stanton Glantz, the veteran anti-tobacco activist behind most of the anti-vaping propaganda that issues from San Francisco?

Glantz is usually described in the media as a professor of medicine, but he isn’t really. He’s never studied medicine in his life; his degrees are all in aeronautical engineering and applied mechanics. His title is a courtesy one because the chair he occupies is in the medicine faculty at UCSF. That chair is the American legacy Foundation Distinguished Professor of Tobacco Control. UCSF let Glantz work there because Legacy, now known as the Truth Initiative, give them a great deal of money every year to support the chair and the university gets to keep half.

This is interesting because Legacy/Truth Initiative get their money from the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, and that flow of cash is slowly drying up as e-cigarettes eat into cigarette sales. Glantz is working hard to either deter smokers from switching to vaping, or get e-cigarette manufacturers corralled into the MSA so they can be forced to contribute to Truth Initiative’s funding.

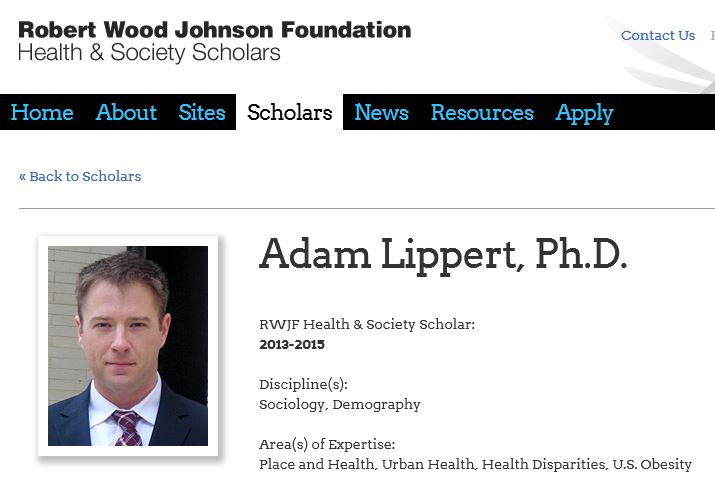

Fake concern about electronic cigarettes sparking an epidemic of teenage nicotine addiction has descended so far into self-parody that it’s become a joke among users. If you want to get any gathering of vapers laughing just shriek, “Think of the chiiildren!!!” – it’s guaranteed to set them off. Research is still being done in a hopeless bid to “prove” it though, including a recent paper in the American Journal of Health Promotion. The author, Adam Lippert, found that adolescent vapers aren’t using e-cigarettes to quit smoking and that stricter regulation is required. This is completely at odds with the far more sophisticated and extensive UK research carried out by ASH and Dr Robert West, but Lippert didn’t list any conflicts of interest so his research is surely worth a closer look?

Not so fast. Lippert didn’t declare any COI, but he’s a Robert Woods Johnson Foundation scholar:

The Robert Woods Johnson foundation is funded by Johnson & Johnson, the world’s largest pharma company and the global distributor of Nicorette smoking cessation products.

Almost every scientist who’s produced negative research about vaping turns out to have received funding from pharmaceutical companies. Is this enough to discredit their research? On its own, no. Many of the scientists who’ve produced positive research on vaping have also received pharma funding, for the simple reason that virtually every medical researcher has. However in the case of e-cig opponents the links are often stronger, and the sums of money larger. And that, I suspect, is a real concern.

I’m not some crazy conspiracy nut who thinks flu vaccines give us flu and pharma companies are all agents of the New World Order. On balance the products of the pharmaceutical industry are a good thing. Modern drugs have had a huge, and positive, impact on health all over the world.

For every lethal aberration like thalidomide or varenicline there are a hundred genuine miracles, like the Salk polio vaccine or synthetic antibiotics. But these are big companies and there are huge profits at stake. If the pharma industry saw one of its big-selling products threatened, as is now happening with nicotine patches and gum, might they resort to unscrupulous tactics to protect sales?

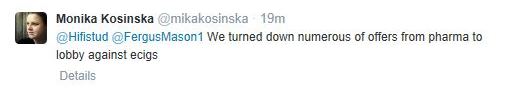

Let’s see what Monika Kosinska, now with the World Health Organisation but formerly general secretary of the European Public Health Alliance, had to say:

That message was sent last year, in the aftermath of the EU’s openly anti-vaping Tobacco Products Directive being rubber-stamped by MEPs. Pharma companies lobbied strongly to make the TPD even more restrictive than it actually is, and they weren’t shy about trying to subvert groups like EPHA to get what they wanted.

It’s not just pharma companies who’re willing to break the rules either. Dr Michael Siegel is a prominent American antismoking activist who in recent years has become critical of many of his former colleagues. Siegel feels that these individuals are less concerned with the truth than they are with pushing their personal agendas and he has a formidable amount of evidence to back this up, including an open admission from Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights that the ideological purity of their campaign takes precedence over scientific integrity. For anyone concerned with real science this is nothing short of terrifying.Who Pays Vaping Advocates?

I know most of the UK’s leading e-cigarette activists through the internet. I’ve met many of them in person, for example at the Global Forum on Nicotine earlier this year (which I wasn’t paid to attend) and I’ve spoken to them about their advocacy work and how it’s financed. The answer is simple – they pay for it themselves.When people like Sarah Jakes or Lorien Jollye attend conferences they aren’t paid to do so. Meanwhile they have to take time off from their real-life jobs to do advocacy. The simple fact is that, far from being hired industry shills, what they do is actually costing them money. Lorien is also a freelance writer and I’ve tried to get her to take on vaping-related work; she absolutely refuses to take money for anything to do with the subject.

Vaping advocates aren’t AstroTurf, and the researchers who’re saying positive things about e-cigarettes aren’t in the pay of the industry. On the other hand most of our opponents have had their research funded by global companies with very deep pockets indeed, and a suspicious habit of getting results that suit the interests of those companies. I’ll leave it up to you to decide who really has a conflict of interest.